“There are moments when the bones of the earth feel as though they’ve rearranged themselves without our permission. I was inexplicably angry. I had never felt rage before. I had read the word rage in books, but I didn’t know what it felt like. My bones were hot. My belly was hot. I kicked a rock across the grass” (When Women Were Dragons, p 83-4).

- Recommended by Sarah B.

When one thinks about becoming a mother, it is usually within the context of learning new skills, trusting instincts, and finding rhythms. Rarely does it involve the notion of losing former parts of oneself or magical transformations…

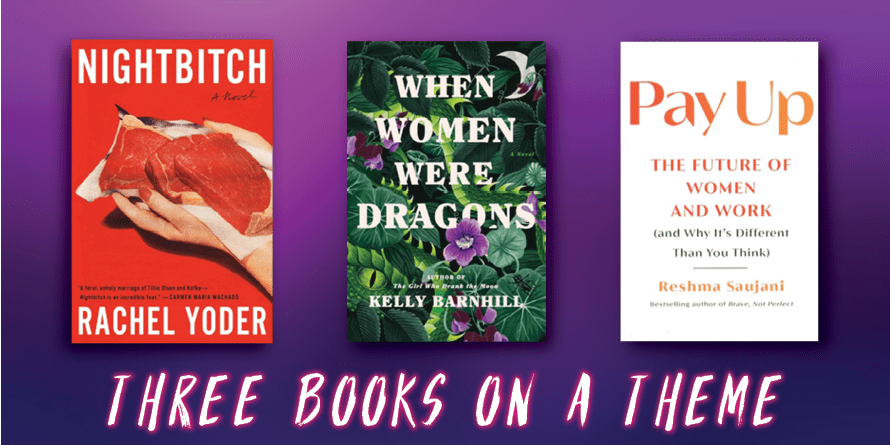

In this story, a mother of a young child thinks she is either turning into a dog or that she may be going crazy. Her teeth feel sharper, she has hair on the back of her neck, and she starts craving raw meat. Lots of raw meat. When she tries to talk to her (mostly absent) husband about these oddities, he thinks she must be joking. But she’s not joking and not appreciative at how unobservant he has become. She goes to the library seeking information and is able to grab two books before her child starts to have a meltdown. One is a medical book about cysts and the other book is A Field Guide to Magical Women by Wanda White. It is described as a mythical ethnography and it becomes the mother’s go to for both recreation and information. When the mother’s aversion to the local mommy group intertwines with her new nocturnal routines, the mother leans in hard on her new beliefs.

This non-traditional story is at times horrific, hysterical, and hopeful. It is a story about motherhood, women, culture, magic, and the possibilities that can manifest at the intertwining and intersections of these realms.

The fact that women have always had the potential to dragon has been hidden by those in power. In 1955, that changes when a mass dragoning occurs and hundreds of thousands of women turn into dragons and fly away. Those who are left behind, not only have to deal with their own trauma, but they must do so with no help from a patriarchal society.

Eight year old Alex knows that she once had an aunt who no longer exists. Her cousin is now her sister. Her mother won’t speak of her aunt anymore and she can expect no help in understanding this new situation.

Years later at school, a doctor and “expert” in feminine health comes to talk about the changes that girls will go through:

“The doctor closed his eyes for a moment. He held up his hand. I learned much later that in 1955, he, too, came home to a dragon destroyed house. I also learned that there had been a message burned into his front door, left for all to see. It said I CONSIDERED EATING YOU, BUT I COULDN’T RISK THE INDIGESTION. THANKS FOR NOTHING. Everyone pretended they didn’t notice it. The whole neighborhood averted their eyes. But everyone saw” (p 69).

The doctor talks about flowers; he talks about butterflies. He talks about transformations and wise choices. He does not talk about dragons or even women’s bodies. But when a girl in Alex’s class menstruates for the first time, the whole class can see the changes that happen to this girl without any choice involved.

Kelly Barnhill agreed to write a short story about dragons for an anthology. And then she listened to Christine Blasey Ford’s testimony to the Senate. Her short story underwent its own metamorphosis and became an extraordinary novel about memory, trauma, and the effects on communities that refuse to talk about the past.

Reshma Saujani, the founder of Girls Who Code https://girlswhocode.com/ and Marshall Plan for Moms https://marshallplanformoms.com/ confronts the “big lie” that American women have been told throughout their lives about working and having families in this country. She examines the evidence of systemic inequalities against women and mothers, in particular, and offers pathways forward for systemic changes to improve the quality of life for all Americans.