Labor Day was established to recognize the struggles working-class people and families have gone through in the history of the United States. Since the Industrial Revolution, workers have had to endure fear, pain, and death to get the rights made available to so many of us today, including paid time off for both illness and fun, health care, and—above all—safe working environments. This was particularly important to factory workers in the earliest days, who could find themselves with permanent disfigurement and fatal injuries any day of the week—including Saturday and Sunday, because there hadn’t been an established Weekend (or even 40 hour work week) yet.

There were a few elements that led to the Labor Movement in the United States as we know it: the invention of steel, the expansion of goods made in factories, and the shelf life of workers as the cities became more populated than the rural areas. Not only was manufacturing long, cruel work, but the machinery necessary to produce anything of note could be hot, heavy, and dangerous.

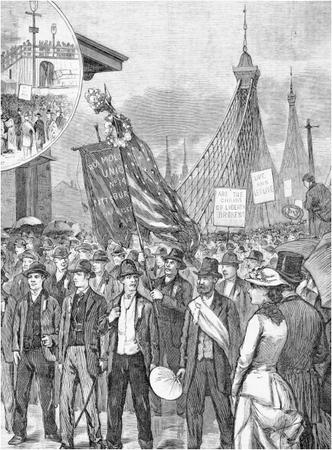

Eventually, workers started organizing, forming groups—Unions—to first demand, and eventually work to negotiate for, certain rights. This included eight-hour days (whereas some factory workers often worked ten or more), safer environments, and fair wages. When unions were finally recognized as legal organizations that acted as the middle man for workers’ rights, they developed and negotiated contracts. If agreed-upon working conditions were not met, or further dangers were seen, the union had the capability to strike (like the Pullman workers). The earliest days of these processes were fraught with danger to both sides; striking workers might set fires and throw stones, usually as a reactive measure to company goons “protecting” property. Unions might be recognized by some employers but not others, thus producing strife across industries.

After decades of violence and corruption, factories and unions became regulated, and Labor Day was recognized as first a state holiday in Oregon, and then a national holiday under Calvin Coolidge. When International Labor Day seemed a little too...international (read socialist) for the Separatist, Capitalist United States, the first Monday in September was designated Labor Day in the US.

As the years passed, the Department of Labor established further rules on workers’ rights, which continue to evolve today. While more and more Americans either decide to or are still required to work on the first Monday of September, it’s a day that helps us remember how far workers’ rights have come for us, and how far we still have to go.

Meanwhile, unions will continue to march in order to acknowledge those who did so in the past, and those who will continue to do so in the future.

Want to know more?

Labor Day Fast Facts (Opposing Viewpoints)

Eight Hours (US History in Context)

Empires of Industry (US History in Context)

The Incomplete, True, Authentic, and Wonderful History of May Day